Nicaragua

There is one brick house in the middle of Comalapa. The windows are square holes that allow the light to come in and the hot breeze to circulate. The sun hitting its zinc roof, at noon, turns the little house into an enormous brick oven, but the people of Comalapa do not mind it. It’s time for the Christmas party.

We arrive at around 11 in the morning, in a van filled with gift bags, toys, 2 big cakes, and a piñata. Some children await outside, the rest are inside the house with their parents. This house is the village’s church. I walk away under a burning sun and photograph it. I want to remember this house. I want to paint it.

As we begin to unload our van , the excitement of the children becomes more audible. They laugh, they run, they clap. My brother, who has invited me, introduces me to the pastor, a woman in her late 60s, wearing shoes and a clean dress. She uses a walker, too. The few men and teen boys that I see around have begun to help our group unload the car. I notice right away, inside the church, the crowd is mostly female. Mothers holding their children, pre-teens holding their newborn siblings, or their own, grandmothers with their little ones on their lap. I ask permission and photograph them. The pastor salutes them and a choir of female voices responds in unison.

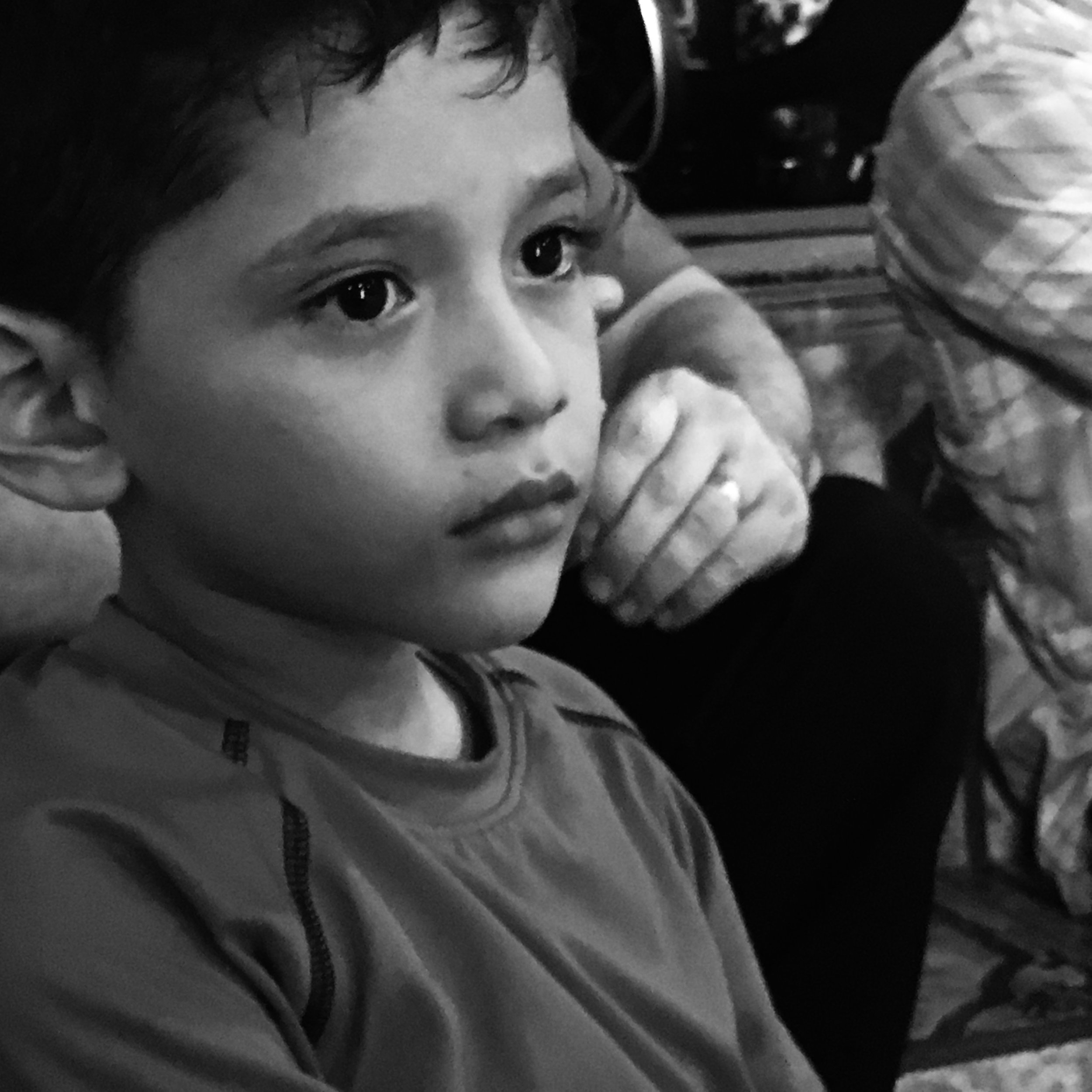

Many of the children at the event are toddlers, some are babies, and some up to 10 years old. The pastor has clarified that the event is only for the “chiquitos.” A couple of teenagers get up to leave the room and she calls on them before they exit the church “But please stay, there is always something for everyone.” Their faces brighten up again, they smile, thank her, and sit back down. They are children, too.

When the singing and praying concludes, the cakes are sliced and shared. Some littles ones line up for a party favor, and then you notice they are the few who are wearing shoes. The rest await, barefoot, to be called to the party favor table. They stretch their necks and jitter in their chairs with excitement. Their little soles are rough and dirty, their toenails broken, their delicate skin burned by the sun. The pastor calls them to line up too, and they rush with excitement. Most of them are wearing a clean set of clothes, nothing fancy, but probably their best. I point my camera at the line, and some of them smile.

The older boys have their working clothes on: an old, oversized t-shirt and shorts, ripped here and there. Many of them work in a landfill nearby sorting trash, but today they have the day off. They can’t be older than 9. I look in their eyes and the light is still there. So I take a photo, I want to capture their expression. Their giggle…that, I’ll just have to remember. I know once this party is over, life will go back to normal for them in Comalapa, but today is party day and all these children want is a slice of cake and a party favor. Some bring the cake home, wrapped in a napkin, to share with their families, others sit down and devour it, saving the baby blue frosting for last.

Everything is dusty in Comalapa; the children’s faces, the church floors, the dirt roads, the mothers’ hopes. Dogs cry in Comalapa, but the children still sing, they still giggle when they hit the piñata, and they lick the fork when they finish their cake. The children make Comalapa exist; their laughter tells the story of their mothers, their absent fathers, their working siblings. At the end, the women come to us and thank us, the children hug us at the hip. I take more photos and we go back to Managua. Comalapa exists in my map, and its people are part of my story.

Para Jaime..